Hemingway Editor 3.0 is a tool which will make your writing one of a kind! It will not only check your grammar, but it will enrich your text, format it and make it ready to share with the world! You can upload directly to Medium and WordPress or you can make it to any web page by exporting to HTML. The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, Volume 3: 1926–1929, featuring many previously unpublished letters, follows a rising star as he emerges from the literary Left Bank of Paris and moves into the American mainstream. Maxwell Perkins, legendary editor at Scribner's, nurtured the young Hemingway's talent, accepting his satirical novel Torrents of. Hemingway Editor 3.0 is a tool which will make your writing one of a kind! It will not only check your grammar, but it will enrich your text, format it and make it ready to share with the world! You can upload directly to Medium and WordPress or you can make it to any web page by exporting to HTML.

Hemingway App has been around for a while, first as a web app and then as a paid desktop app that had seen one major update in its two or so years of existence. We reviewed the original desktop app as well as the 2.0 update, concluding in the first case that it may not be worth the cost and that the update had too many compromises to go along with its price hike. How about the newest version? The price is still on the higher end of plain-text writing apps, but new features and improvements make it worth considering.

Hemingway Editor makes your writing bold and clear. Hemingway Editor highlights common errors. Use it to catch wordy sentences, adverbs, passive voice, and dull, complicated words. Use Hemingway Editor wherever you write - on the train, at the beach, or in a coffee shop with spotty Wi-Fi. As long as you have your computer, you'll have Hemingway.

We clearly don’t have great timing here at GTT. It was only about two weeks ago that we finally got around to our review of Hemingway App 2.0. To make up for that, we’re getting this 3.0 review out quickly, just 3 days after it was announced to the public.

Overview

The creators of Hemingway—who work on it more as a side gig—say that this update involved rewriting the app entirely. This does risk stability issues, especially when they have not shown a propensity to issue bugfix updates. With that said, it’s probably a risk worth taking when you consider how limited the former versions were.

Let’s look at a rundown of the new features:

- Publish to WordPress and Medium from the app

- Export to PDF, with or without Hemingway’s highlights

- Distraction free mode with and without highlighting

- Import from HTML and Markdown

- Support for multiple documents being open at once (seriously, this wasn’t possible before)

- Interface tweaks

Interface

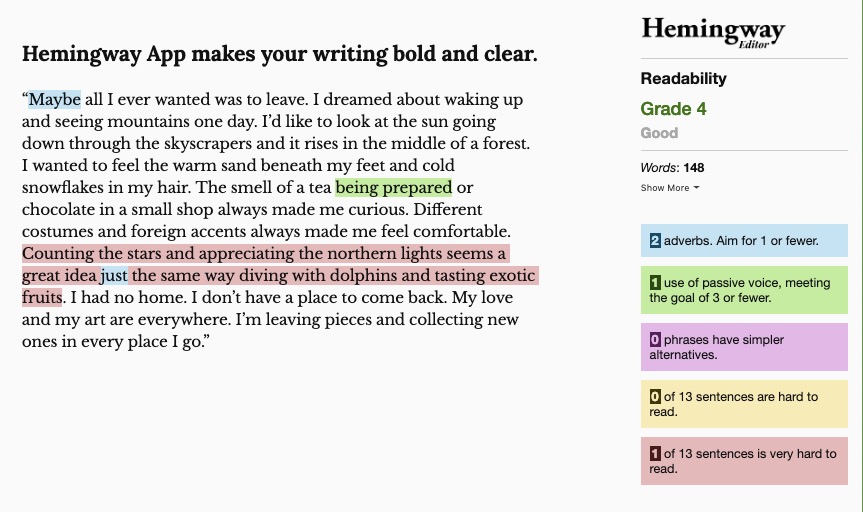

Let’s start with the bare aesthetics. Hemingway gets a minor facelift, at least at first glance. Here’s a look at it with a writing sample added:

It is simple but pleasant enough, though I should add that I am no fan of the serif font—it communicates “fancy” but designers know that serif fonts are best suited for print, not screens. For the sake of completeness, let’s have a look at the previous two versions as well.

Hemingway 2.0:

Hemingway 1.0:

I don’t think I’m out on a limb in saying that the newest edition, 3.0, looks best. Beyond that, though, there’s another aspect of the interface that deserves attention. I can’t really show it to you, but the app is much smoother in its animations and responsiveness than the earlier versions. It feels like a better-made piece of software.

It’s also worth noting that the Readability grade has changed with the same writing sample, suggesting more under the hood changes as well.

Next I want to show the tooltips that explain why things are highlighted. This has been present in some form in the previous versions, but in certain cases the tooltips are now more specific and even offer a shortcut to fix the issue with a button press.

In the above example, Hemingway is complaining that “accompany” is a needlessly complex word. It suggests using “with” or “go with” and it will replace the word “accompany” with one of those if you click one of the buttons presented. Note that you’ll have to use your brain a bit with these suggestions, since “with” would not make sense in the sentence, though “go with” would work well.

The suggestions for adverbs (as above) are less specific, since Hemingway tells you to use a different verb rather than modifying it with an adverb. On the other hand, it is often wise to do as its alternative suggests: Just get rid of the adverb and leave everything else.

PDF Export

It’s important to remember what sets Hemingway apart: The editing suggestions. That’s why, at least in the abstract, I like that this update includes the ability to export a highlighted version of the document to PDF format. This allows you to, for instance, share the suggestions with a collaborator who doesn’t have Hemingway.

You can see an example of such a document by clicking here. You don’t have any control over things like the font or full-document properties, like the margins and so on. Another potential drawback is that while the highlights are there, you will need to know ahead of time what they mean—there is no explanation embedded within.

I still think it is a good new feature, but I would like to see more options added in the future.

Publish to WordPress, Medium

As a disclaimer, I cannot test this easily but I felt it was worthwhile to show you how this works. It appears that Hemingway is using the same API that several other apps with this functionality use to publish to WordPress.

Clearly, you don’t need to be a computer expert to get your writing from Hemingway to your WordPress site. It would be a good idea, though, to save it in draft format so you can make sure everything renders correctly on your site. Hemingway also doesn’t have the ability to insert images in an easy way, not to mention some of the metadata you may want to add. This can be a useful part of the workflow, but I would suggest caution in publishing straight from the app.

Publishing to Medium is very similar, but you do need to get an “integration token” first rather than entering login information. Medium posts probably lend themselves to easier publishing straight from Hemingway since multimedia is less common and users tend not to use tagging and the like as much as self-hosted WordPress sites.

Exporting to Markdown, HTML

To test the ability to export to Markdown and HTML, I wanted to have a formatted document, since that’s where Hemingway would be likely to trip up. Here is how it looks in Hemingway:

First, let’s look at the Markdown produced by the export function.

That appears perfect and renders correctly on this site if I paste it into a post.

Let’s check the HTML:

There are a couple of extraneous , but that is pretty typical of any text-to-HTML converter, like WordPress’s visual editor. Otherwise, this is correct.

Final thoughts

This is a much more polished app than the previous iterations. For some, this will push them over the top in terms of deciding to buy it. Make no mistake, though, if you buy it, get it for the editing suggestions. Even with improvements, it is still far behind other prose-focused text editors in every other regard.

Is $20 too much? I don’t think I’d buy it today at that price, especially when I know I can paste text into the free web app to get the editing suggestions. For others of you, the $20 will feel worth it—either because you value the editing suggestions and new features so much or because $20 doesn’t feel like much money for software.

Learn more or buy it here.

I’ve been using the Hemingway App to try to improve my posts. At the same time I’ve been trying to find ideas for small projects. I came up with the idea of integrating a Hemingway style editor into a markdown editor. So I needed to find out how Hemingway worked!

Getting the Logic

I had no idea how the app worked when I first started. It could have sent the text to a server to calculate the complexity of the writing, but I expected it to be calculated client side.

Opening developer tools in Chrome ( Control + Shift + I or F12 on Windows/Linux, Command + Option + I on Mac) and navigating to Sources provided the answers. There, I found the file I was looking for: hemingway3-web.js.

This code is in a minified form, which is a pain to read and understand. To solve this, I copied the file into VS Code and formatted the document (Control+ Shift + I for VS Code). This changes a 3-line file into a 4859-line file with everything formatted nicely.

Exploring the Code

I started to look through the file for anything that I could make sense of. The start of the file contained immediately invoked function expressions. I had little idea of what was happening.

This continued for about 200 lines before I decided that I was probably reading the code to make the page run (React?). I started skimming through the rest of the code until I found something I could understand. (I missed quite a lot that I would later find through finding function calls and looking at the function definition).

The first bit of code I understood was all the way at line 3496!

And amazingly, all these functions were defined right below. Now I knew how the app defined adverbs, qualifiers, passive voice, and complex words. Some of them are very simple. The app checks each word against lists of qualifiers, complex words, and passive voice phrases. this.getAdverbs filters words based on whether they end in ‘ly’ and then checks whether it’s in the list of non-adverb words ending in ‘ly’.

The next bit of useful code was the implementation of highlighting words or sentences. In this code there is a line:

‘hardSentences’ was something I could understand, something with meaning. I then searched the file for hardSentences and got 13 matches. This lead to a line that calculated the readability stats:

Now I knew that there was a readability parameter in both stats and i.default. Searching the file, I got 40 matches. One of those matches was a getReadabilityStyle function, where they grade your writing.

There are three levels: normal, hard and very hard.

“Normal” is less than 14 words, “hard” is 10–14 words, and “very hard” is more than 14 words.

Now to find how to calculate the reading level.

I spent a while here trying to find any notion of how to calculate the reading level. I found it 4 lines above the getReadabilityStyle function.

That means your score is 4.71 * average word length + 0.5 * average sentence length -21.43. That’s it. That is how Hemingway grades each of your sentences.

Other Interesting Things I Found

- The highlight commentary (information about your writing on the right hand side) is a big switch statement. Ternary statements are used to change the response based on how well you’ve written.

- The grading goes up to 16 before it’s classed as “Post-Graduate” level.

What I’m going to do with this

I am planning to make a basic website and apply what I’ve learned from deconstructing the Hemingway app. Nothing fancy, more as an exercise for implementing some logic. I’ve built a Markdown previewer before, so I might also try to create a writing application with the highlighting and scoring system.

Having figured out how the Hemingway app works, I then decided to implement what I had learnt to make a much simplified version.

I wanted to make sure that I was keeping it basic, focusing on the logic more that the styling. I chose to go with a simple text box entry box.

Challenges

1. How to assure performance. Rescanning the whole document on every key press could be very computationally expensive. This could result in UX blocking which is obviously not what we want.

2. How to split up the text into paragraphs, sentences and words for highlighting.

Possible Solutions

- Only rescan the paragraphs that change. Do this by counting the number of paragraphs and comparing that to the document before the change. Use this to find the paragraph that has changed or the new paragraph and only scan that one.

- Have a button to scan the document. This massively reduces the calls of the scanning function.

2. Use what I learnt from Hemingway — every paragraph is a <p> and any sentences or words that need highlighting are wrapped in an internal <span> with the necessary class.

Building the App

Recently I’ve read a lot of articles about building a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) so I decided that I would run this little project the same. This meant keeping everything simple. I decided to go with an input box, a button to scan and an output area.

This was all very easy to set up in my index.html file.

Now to start on the interesting part. Now to get the Javascript working.

The first thing to do was to render the text from the text box into the output area. This involves finding the input text and setting the output’s inner html to that text.

Next is getting the text split into paragraphs. This is accomplished by splitting the text by ‘n’ and putting each of these into a <p> tag. To do this we can map over the array of paragraphs, putting them in between <p> tags. Using template strings makes doing this very easy.

Whilst I was working though that, I was becoming annoyed having to copy and paste the test text into the text box. To solve this, I implemented an Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE) to populate the text box when the web page renders.

Now the text box was pre-populated with the test text whenever you load or refresh the web page. Much simpler.

Highlighting

Now that I was rendering the text well and I was testing on a consistent text, I had to work on the highlighting. The first type of highlighting I decided to tackle was the hard and very hard sentence highlighting.

The first stage of this is to loop over every paragraph and split them into an array of sentences. I did this using a `split()` function, splitting on every full stop with a space after it.

From Heminway I knew that I needed to calculate the number of words and level of each of the sentences. The level of the sentence is dependant on the average length of words and the average words per sentence. Here is how I calculated the number of words and the total words per sentence.

Using these numbers, I could use the equation that I found in the Hemingway app.

With the level and number of words for each of the sentences, set their difficulty level.

Hemingway Editor 3 Free

This code says that if a sentence is longer than 14 words and has a level of 10 to 14 then its hard, if its longer than 14 words and has a level of 14 or up then its very hard. I used template strings again but include a class in the span tags. This is how I’m going to define the highlighting.

The CSS file is really simple; it just has each of the classes (adverb, passive, hardSentence) and sets their background colour. I took the exact colours from the Hemingway app.

Once the sentences have been returned, I join them all together to make each of the paragraphs.

Hemingway Editor 3.0 Reviews

At this point, I realised that there were a few problems in my code.

- There were no full stops. When I split the paragraphs into sentences, I had removed all of the full stops.

- The numbers of letters in the sentence included the commas, dashes, colons and semi-colons.

My first solution was very primitive but it worked. I used split(‘symbol’) and join(‘’) to remove the punctuation and then appended ‘.’ onto the end. Whist it worked, I searched for a better solution. Although I don’t have much experience using regex, I knew that it would be the best solution. After some Googling I found a much more elegant solution.

With this done, I had a partially working product.

The next thing I decided to tackle was the adverbs. To find an adverb, Hemingway just finds words that end in ‘ly’ and then checks that it isn’t on a list of non-adverb ‘ly’ words. It would be bad if ‘apply’ or ‘Italy’ were tagged as adverbs.

To find these words, I took the sentences and split them into an arary of words. I mapped over this array and used an IF statement.

Whist this worked most of the time, I found a few exceptions. If a word was followed by a punctuation mark then it didn’t match ending with ‘ly’. For example, “The crocodile glided elegantly; it’s prey unaware” would have the word ‘elegantly;’ in the array. To solve this I reused the .replace(/^a-z0-9. ]/gi,””) functionality to clean each of the words.

Another exception was if the word was capitalised, which was easily solved by calling toLowerCase()on the string.

Now I had a result that worked with adverbs and highlighting individual words. I then implemented a very similar method for complex and qualifying words. That was when I realised that I was no longer just looking for individual words, I was looking for phrases. I had to change my approach from checking if each word was in the list to seeing if the sentence contained each of the phrases.

To do this I used the .indexOf() function on the sentences. If there was an index of the word or phrase, I inserted an opening span tag at that index and then the closing span tag after the key length.

With that working, it’s starting to look more and more like the Hemingway editor.

The last piece of the highlighting puzzle to implement was the passive voice. Hemingway used a 30 line function to find all of the passive phrases. I chose to use most of the logic that Hemingway implemented, but order the process differently. They looked to find any words that were in a list (is, are, was, were, be, been, being) and then checked whether the next word ended in ‘ed’.

I looped though each of the words in a sentence and checked if they ended in ‘ed’. For every ‘ed’ word I found, I checked whether the previous word was in the list of pre-words. This seemed much simpler, but may be less performant.

With that working I had an app that highlighted everything I wanted. This is my MVP.

Then I hit a problem

As I was writing this post I realised that there were two huge bugs in my code.

These will only ever find the first instance of the key or match. Here is an example of the results this code will produce.

‘Perhaps’ and ‘been marked’ should have been highlighted twice each but they aren’t.

To fix the bug in getQualifier and getComplex, I decided to use recursion. I created a findAndSpan function which uses .indexOf() to find the first instance of the word or phrase. It splits the sentence into 3 parts: before the phrase, the phrase, after the phrase. The recursion works by passing the ‘after the phrase’ string back into the function. This will continue until there are no more instances of the phrase, where the string will just be passed back.

Something very similar had to be done for the passive voice. The recursion was in an almost identical pattern, passing the leftover array items instead of the leftover string. The result of the recursion call was spread into an array that was then returned. Now the app can deal with repeated adverbs, qualifiers, complex phrases and passive voice uses.

Statistics Counter

The last thing that I wanted to get working was the nice line of boxes informing you on how many adverbs or complex words you’d used.

To store the data I created an object with keys for each of the parameters I wanted to count. I started by having this variable as a global variable but knew I would have to change that later.

Now I had to populate the values. This was done by incrementing the value every time it was found.

The values needed to be reset every time the scan was run to make sure that values didn’t continuously increase.

With the values I needed, I had to get them rendering on the screen. I altered the structure of the html file so that the input box and output area were in a div on the left, leaving a right div for the counters. These counters are empty divs with an appropriate id and class as well as a ‘counter’ class.

With these divs, I used document.querySelector to set the inner html for each of the counters using the data that had been collected. With a little bit of styling of the ‘counter’ class, the web app was complete. Try it out here or look at my code here.